By Professor Giorgi Pkhakadze

Chair, Public Health Institute of Georgia (PHIG)

Introduction

We are living through one of the most defining humanitarian and public health crises of our time. As conflict, climate change, and socioeconomic instability displace millions, the burden falls heavily on national health systems that are often unprepared to meet the needs of increasingly diverse populations. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), there were over 281 million international migrants in 2022, with more than 36 million refugees and asylum seekers. By mid-2024, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that over 117 million individuals will be forcibly displaced—an alarming figure that underscores both a humanitarian emergency and a global policy failure.

This mass movement of people presents both an obligation and an opportunity: to build stronger, fairer, and more inclusive healthcare systems. Refugees and migrants bring with them a wealth of resilience and potential, but also face deep-seated barriers to accessing care, from legal exclusion to linguistic and cultural divides. The gaps are most evident in frontline service delivery, where health workers are often left without the training or tools to respond effectively to the unique health profiles and rights of displaced populations.

At the same time, governments around the world are struggling to maintain equity and quality in health service provision, even for their own citizens. In this context, ensuring that health professionals are equipped to serve everyone—not just those who fall within traditional citizenship models—is not only a matter of ethics, but a strategic necessity.

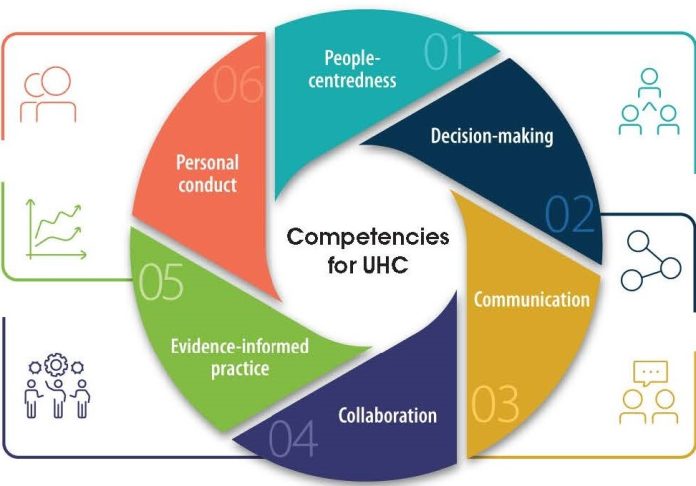

It is within this complex, high-stakes environment that the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Competency Standards for Refugee and Migrant Health (GCS). The GCS are designed to close the knowledge and skills gap in healthcare delivery to refugees and migrants. More importantly, they provide a structured framework that governments can use to regulate training, licensing, and professional development in alignment with equity-focused international goals such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

This article outlines why the adoption of the GCS should be seen not just as an educational initiative but as a legal and policy imperative. By showcasing real-world implementation models—from Canada and Kenya to the European Union and Georgia—it makes the case for urgent and systemic reform to embed the GCS into national legislation, accreditation systems, and public health strategies.

Migration, whether voluntary or forced, intersects with all aspects of health—from access and quality of care to the social determinants that shape well-being. Refugees and migrants often face disproportionate health risks, including poor access to healthcare, language and cultural barriers, mental health burdens, and heightened exposure to infectious diseases. Structural exclusion from national health plans, fragmented services, and a lack of trained providers exacerbate these disparities and violate basic human rights.

Despite international commitments to Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), many national health systems remain ill-prepared to deliver inclusive, high-quality, and culturally responsive services to mobile and displaced populations. These vulnerabilities are not limited to low-income countries. In high-income regions such as Europe and North America, the absence of migration-competent training is still a barrier to equitable care.

The situation calls for urgent, coordinated, and legally grounded action. The World Health Organization (WHO) responded with the introduction of the Global Competency Standards for Refugee and Migrant Health (GCS)—a transformative policy and education framework designed to equip all health workers with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to deliver inclusive and rights-based care.

More than a guideline, the GCS represent a paradigm shift. They call for health worker regulation, institutional policy reform, and multi-level governance to embed equity into every level of care. For the GCS to be impactful, they must become a legal and policy imperative—not merely a best practice. This article presents an evidence-based argument for the integration of competency standards into national laws and professional licensing, using global, regional, and national examples to show how it can be done—and why it must be done now.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored these challenges. Displaced populations were often left out of national vaccination and response plans, while front-line healthcare workers reported uncertainty and discomfort in treating patients from unfamiliar backgrounds. These experiences exposed an urgent need to equip health professionals with the knowledge, skills, and values necessary to provide equitable, culturally responsive, and trauma-informed care.

In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the Global Competency Standards for Refugee and Migrant Health (GCS)—a framework that outlines core competencies for all health workers interacting with these populations. These standards aim to institutionalize person-centered, rights-based, and inclusive care into health systems worldwide. However, for the GCS to make a lasting impact, they must be integrated into national policies, legislation, and professional regulation frameworks.

This article argues that training for all health workers must be recognized not just as good practice—but as a legal and policy imperative. By analyzing case studies from Canada, Kenya, the European Union, and Georgia, it presents a roadmap for turning competency standards into enforceable tools that strengthen equity and accountability in healthcare systems.

Health worker training on WHO Global Competency Standards

Health worker training on WHO Global Competency StandardsGlobal Precedents: Canada and Kenya

Global implementation of the Global Competency Standards (GCS) is gaining momentum, with Canada and Kenya standing out as frontrunners in translating policy into action. These countries have demonstrated that integrating GCS into health licensing and training structures is not only feasible but also impactful.

In Canada, provinces such as Ontario and British Columbia are incorporating migration-sensitive competencies into licensing requirements and Continuing Medical Education (CME) criteria. A 2023 policy review from the Canadian Medical Association found that over 60% of surveyed healthcare providers supported mandatory training in refugee and migrant health, particularly in urban centers where 35% of the population consists of first-generation immigrants. In Ontario alone, more than 250,000 healthcare workers now have access to GCS-aligned training through provincial CME platforms.

Kenya provides another compelling example. The Ministry of Health, in collaboration with WHO and IOM, has piloted GCS-based training modules in five counties that host large refugee populations, including Turkana, Garissa, and Nairobi. According to a 2022 report from Kenya’s Department of Health Workforce Development, over 12,000 health workers received competency-based training between 2021 and 2023. Furthermore, the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council is reviewing amendments that would make refugee health competencies a requirement for license renewal in selected regions.

These efforts are grounded in national health workforce strategies that recognize the increasing demands placed on front-line providers. Both countries have integrated GCS training into professional development pathways and linked them to measurable performance indicators such as patient satisfaction, service equity scores, and treatment adherence rates.

By embedding GCS into licensing, CME, and curriculum requirements, Canada and Kenya show how structural change can support both professional growth and health equity. Their experiences offer clear lessons for other nations looking to institutionalize migration health competencies within national regulatory systems.

Migrant medical camp

Migrant medical campEuropean Union and WHO Europe: From Policy to Law

Across the European Union, the drive to institutionalize the Global Competency Standards (GCS) is gaining traction. The need is urgent: according to Eurostat, over 2.9 million people sought asylum in EU+ countries between 2021 and 2023, while millions more migrated for economic or humanitarian reasons. Despite this, a 2022 European Public Health Alliance report found that only 38% of frontline healthcare providers had received any form of migration health training.

Several Member States have taken bold steps toward rectifying this. In Germany, state governments are integrating cultural and linguistic competency modules aligned with the GCS into public health postgraduate programs. In Sweden, the National Board of Health and Welfare has made cultural competence training a core component of nurse licensing renewal. The Netherlands has launched a national platform that incorporates GCS principles into continuing professional development (CPD) for primary care physicians, with 8,200 registrants in its first year.

Beyond country-level efforts, the European Commission is enabling large-scale harmonization. The European Skills Agenda explicitly supports lifelong learning and cross-border recognition of healthcare training—creating a pathway to embed GCS into regional qualification frameworks. Meanwhile, the EU4Health Programme has allocated over €5.3 billion through 2027, part of which supports training programs for inclusive health access, including migrant populations.

The WHO Regional Office for Europe has complemented these policy shifts by developing implementation guidance for ministries and academic institutions, and by establishing regional benchmarks to track the uptake of migration-sensitive competencies.

As a senior health official from Romania noted during the 2024 WHO Europe Migration Health Forum: “The GCS are not just a technical tool—they are a human rights framework. Embedding them in law is about fulfilling our ethical and legal commitments to all who reside in Europe.”

To accelerate progress, it is time for the European Commission to consider a directive mandating the integration of GCS within national accreditation and licensing bodies. Such harmonization would ensure consistency across health systems while upholding the rights and dignity of displaced persons throughout the region.

Georgia: A Strategic Legal Recommendation

In Georgia, the case for institutionalizing the Global Competency Standards (GCS) has become increasingly urgent. As the country progresses toward integration with the European Union and continues to navigate domestic health system reforms, aligning with international human rights and health equity frameworks is both strategic and essential.

Georgia is a transit and host country for thousands of refugees, asylum seekers, migrants, and ethnic minorities. According to data from the Public Service Development Agency, over 35,000 foreign nationals were residing in Georgia with temporary or permanent status as of 2023, including displaced individuals from Ukraine, Afghanistan, and neighboring regions. The Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons also supports over 280,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) from previous conflicts. These populations have unique healthcare needs—needs that cannot be addressed without specific, structured training for frontline providers.

The Public Health Institute of Georgia (PHIG), in partnership with David Tvildiani Medical University (DTMU), has initiated a nationwide advocacy and technical assistance campaign to promote GCS uptake. These efforts include faculty development workshops, public health forums, academic curriculum reforms, and pilot GCS-aligned modules across undergraduate and postgraduate programs.

To achieve systematic integration, PHIG and DTMU jointly recommend that the Ministry of Health of Georgia undertake the following legal and institutional actions:

– Enact a ministerial decree mandating that all healthcare providers complete a certified GCS training module during license renewal cycles.

– Integrate GCS into CME accreditation frameworks, making it a requirement for re-licensure and career progression within the public health system.

– Revise national curriculum standards for medical and health sciences universities to include compulsory modules on refugee and migrant health, in collaboration with the National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement.

– Establish a national taskforce led by the Ministry of Health, with technical support from PHIG and WHO Georgia, to coordinate the monitoring, evaluation, and continuous improvement of GCS implementation.

Early results from PHIG’s pilot workshops are promising. In 2024 alone, over 420 healthcare professionals from 3 regions (Tbilisi, Adjara, and Imereti) participated in introductory training, with 92% reporting increased confidence in addressing migration-related health challenges. Further, several university departments have formally requested PHIG’s support in integrating GCS modules into upcoming academic years.

Legal codification of these standards would also support Georgia’s compliance with global and regional commitments—including the Global Compact for Migration, the WHO European Programme of Work, and EU-aligned human rights frameworks.

Making GCS implementation mandatory is not only a technical upgrade—it is a moral and strategic investment in a just, responsive, and inclusive health system that leaves no one behind.

Leveraging the SDGs for Policy Advocacy

Advancing the legal and policy integration of the Global Competency Standards (GCS) can be strategically reinforced through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—a globally endorsed framework with universal appeal and accountability. By aligning advocacy for GCS with national and international SDG commitments, stakeholders can increase political will, attract donor support, and mobilise cross-sectoral action.

Several SDGs directly support the integration of GCS:

– SDG 3.8 calls for Universal Health Coverage (UHC), emphasising access to quality essential health services for all, including migrants and refugees. GCS enable health workers to meet this target by strengthening skills in culturally appropriate, non-discriminatory care.

– SDG 4.7 promotes inclusive, equitable education and lifelong learning. Integrating GCS into pre-service and in-service health training ensures that the health workforce is prepared from the start.

– SDG 10.2 calls for the social, economic, and political inclusion of all, regardless of status. Competency-based approaches directly address systemic barriers that marginalise migrants in healthcare systems.

– SDG 16.6 aims to develop effective, accountable, and transparent institutions. Making GCS mandatory through professional regulation strengthens institutional performance and public trust.

This alignment is not abstract. In fact, countries such as Portugal and Slovenia have successfully linked health equity initiatives—including GCS-based education pilots—to their national SDG implementation strategies. In Portugal, health authorities use SDG 3 and 10 indicators to justify inclusive health education reforms to the Ministry of Finance. Similarly, Slovenia’s National Development Strategy cross-references SDG indicators to prioritise workforce training for migrant-inclusive services.

International platforms also reinforce this approach. The WHO SDG Partnership Platform and the EU4Health Programme provide not only funding but technical guidance to embed SDG-aligned health strategies—including GCS—in national plans.

Policymakers and advocates should frame legislative proposals around SDG indicators. For example:

– “Mandating GCS in licensing aligns with SDG 3.8 to ensure quality healthcare access for all.”

– “Including migration health in university curricula supports SDG 4.7 for inclusive education.”

By anchoring GCS within this universally accepted development framework, countries not only ensure policy coherence but also elevate the legitimacy and urgency of inclusive health reform.

Migrant medical camp

Migrant medical campConclusion

The institutionalisation of the Global Competency Standards (GCS) is no longer a matter of preference or policy aspiration—it is a necessary evolution in global health governance. As nations confront the realities of record displacement, systemic inequities, and workforce challenges, the GCS provide a concrete, adaptable framework to ensure that no one is excluded from high-quality, respectful care.

Evidence from Canada, Kenya, the European Union, and Georgia shows that embedding GCS into legal and professional frameworks has a multiplier effect. It not only raises standards of care but fosters a workforce that is ethically grounded, clinically competent, and socially responsive. Countries that institutionalize GCS benefit from stronger health outcomes, improved public trust, and greater alignment with international health and human rights obligations.

Georgia’s leadership, particularly through the collaborative efforts of PHIG and David Tvildiani Medical University, demonstrates that national institutions can catalyze regional transformation. These localized, evidence-driven approaches serve as blueprints for broader WHO European Region implementation and offer replicable models for middle-income countries globally.

Legislative integration of GCS also ensures sustainability. When tied to licensing, accreditation, and monitoring systems, competency becomes a permanent pillar—not a pilot project. Furthermore, aligning legal reforms with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enhances legitimacy, encourages multisectoral partnerships, and opens doors to strategic funding.

The pathway forward is clear:

- GCS must be codified in professional licensing and training.

- Ministries of Health must champion legal reform and interministerial collaboration.

- Donors and technical partners must align funding to support GCS implementation.

- Academic institutions must drive innovation in curriculum and assessment.

This is not just about training healthcare providers—it is about embedding dignity, empathy, and equity into the fabric of public health.

As the world strives toward Universal Health Coverage and global equity, GCS stand as a moral, strategic, and professional imperative.

The time to legislate for inclusion is now. The time to build systems that heal without exclusion is now.

Competency is not just a qualification—it is a reflection of our shared humanity.

Professor Giorgi Pkhakadze, MD, MPH, PhD

Professor and Head of Department at David Tvildiani Medical University (DTMU), Chair of the Public Health Institute of Georgia (PHIG), and Official Representative of Accreditation Canada in Georgia. He is a World Health Organization (WHO) consultant on health and migration, former Member of the UN Secretary-General’s Independent Accountability Panel for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, and a current Technical Advisor to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and former technical expert of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFTAM).

With over 25 years of experience in global and national public health systems, Professor Pkhakadze is a leading advocate for advancing equity, accountability, and quality of care, particularly for refugees, migrants, and vulnerable populations worldwide.

🔗 More at: www.asf-france.fr

📬 Contact: [email protected]

📱 #drpkhakadze #გიორგიფხაკაძე #HealthForAll #MigrationHealth #AccountabilityMatters

References

1. World Health Organization. Refugee and Migrant Health: Global Competency Standards for Health Workers. Geneva: WHO; 2021. Available from: [https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030626](https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030626) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

2. International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2022. Geneva: IOM; 2022. Available from: [https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2022](https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/wmr-2022) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

3. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023. Geneva: UNHCR; 2024. Available from: [https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/667e2e7e4/global-trends-forced-displacement-2023.html](https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/667e2e7e4/global-trends-forced-displacement-2023.html) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

4. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health of Migrants: Access and Outcomes in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2021. Available from: [https://www.oecd.org/migration/health-of-migrants-report-2021.htm](https://www.oecd.org/migration/health-of-migrants-report-2021.htm) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

5. European Commission. European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience. Brussels: European Commission; 2020. Available from: [https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1223](https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1223) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

6. European Commission. EU4Health Programme 2021–2027. Brussels: European Commission; 2021. Available from: [https://health.ec.europa.eu/funding/eu4health-programme-2021-2027\_en](https://health.ec.europa.eu/funding/eu4health-programme-2021-2027_en) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

7. World Health Organization. European Programme of Work, 2020–2025 – United Action for Better Health. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Available from: [https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2020-1437-41173-56444](https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2020-1437-41173-56444) (Accessed: 23 April 2025)

8. Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia. Georgia Health Sector Reform Strategy 2024–2028. Tbilisi: Ministry of Health; 2024. [Internal policy draft – citation pending public release]

7 months ago

80

7 months ago

80

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  Georgian (GE) ·

Georgian (GE) ·